Isabel Parker

Isabel is the Executive Director of the Digital Legal Exchange, a not-for-profit organisation with a mission to accelerate the digital transformation of corporate legal teams. Before joining the Exchange, Isabel was Chief Legal Innovation Officer at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer.

Isabel is a passionate advocate for change in the legal sector. Her first book,’Successful Digital Transformation in Law Firms: a question of culture’ was published in November 2021.

So far, this has been another turbulent year. The last two months have been dominated by the war in Ukraine, with law firms and corporate legal teams scrabbling to recalibrate their client relationships in the light of the Russian invasion and to manage the impact on their people. The news of the invasion hit like a tsunami, just as the Western world was emerging from the worst ravages of Coronavirus and beginning to hope for a return to a more stable economic future. The legal industry, still reeling from the radical shift to remote and hybrid working catalysed by the pandemic, has been compelled once again to pivot quickly in response to unforeseen events.

In this post, I explain why adaptability is a critical success factor for managing change, explore why law firms in particular find change challenging, and suggest that they need to address this issue if they are to future proof their business model.

The legal services sector has, historically, been slow to change. The reasons for this are complex and multifaceted, ranging from organisational (the traditional law firm partnership model is not well adapted to business model change); cultural (the mantle of ‘lawyer exceptionalism’ allows some lawyers to exempt themselves from change that impacts their clients); and financial (when a lot of money is being made, there is no incentive to challenge the status quo). However, nothing catalyses change more quickly than a crisis, and we have not been short on crises over the past two years. This is not a blip, but a long-term trend that organisations and individuals alike will need to learn to live with. John Kotter (the godfather of successful organisational change) observes in his most recent book that the Coronavirus pandemic is not a “once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon”, but a spike in a greater trend of accelerating global change. Managing uncertainty, Kotter argues, is now the single most significant challenge for all organisations:

… a gap is clearly growing between the amount of change happening around us and the change we are successfully, smartly implementing in most of our organizations and lives … this disconnect is increasingly dangerous, especially when people have been convinced that … continuous incremental improvements are all that is needed.

Managing change is not an indulgence, but an organisational necessity for corporates and law firms alike. The ability to respond to and implement change successfully is what will differentiate leading organisations from the rest of the pack. This has implications for how organisations are structured, managed and led, and for the kind of culture they need to create and nurture.

Historically, the corporate culture that we thought indicative of superior performance was described as ‘strong’, characterised by the existence of a defined strategy set by a charismatic leadership team, tight hierarchical management controls and an effective chain of command. A strong culture meant that everyone was working to the same playbook. This homogeneity generated institutional cohesion and pride, and enabled great teamwork.

Law firms – particularly so-called ‘Big Law’ firms – have been very effective in creating strong cultures. In our world of rapidly accelerating change, however, the litmus test for competitive success may no longer turn on whether the culture of an organisation is ‘strong’. Kotter’s research into the correlation between corporate results and culture demonstrates that:

… there was some relationship – but not much – between ‘strong’ cultures and three measures of decade-long financial results. Strong cultures were extremely influential, but we found it was quite possible for a firm to have what might be called a strong but toxic culture, where norms driving behavior and shared values were powerful but not the slightest bit competitively helpful. [p.106]

A better indicator of superior performance could be found in organisations that displayed the following cultural attributes:

At their core, they highly valued the interests of all the enterprises’ major constituencies, particularly customers, stockholders, and employees, and thus managers and executives paid close attention to these factors … we called these winning cultures ‘adaptive’. [pp 107 – 108]

Creating an adaptive culture requires an organisation to take a long view, to resist a focus on short-term gains, and to listen attentively to all its stakeholders (customers and employees in particular). This effort cannot be delegated to a small senior leadership team. To be effective, it must be atomised through the entire organisation. Kotter’s research shows that adaptive organisations:

… encourage and support leadership from many people, not just from a few of their peers at the top of an organization … they use small, highly select groups to attack certain change tasks. Yet they also heavily rely on the diverse many – a group big enough and with the breadth of information and contacts both to figure out what changes are needed and to execute them despite human nature and organizational barriers. [p. 57]

What does a reliance on “the diverse many” mean for law firms and corporate legal teams? It means encouraging change leadership at every level of the organisation, rather than delegating the change effort to a senior leadership team, board, subset of partners or innovation team. Perhaps this sounds like a simple fix, but those working in change roles in law firms and corporate legal teams know that the reality on the ground makes this challenging to implement.

Law firms and corporate legal teams are facing major issues with employee retention. Whilst the reasons for the Great Resignation in other industries are somewhat opaque, the reasons in legal are all too clear. Both the legal and national press have given extensive coverage to three aspects of law firm life, in particular:

- high work volumes (resulting in punishing working hours);

- talent wars (lateral poaching running rife and eyewatering lawyer salary hikes); and

- cultural fallout (numerous stories of lawyer burnout, serious mental health issues, and stress).

The common thread running through all this coverage is that law firms – and corporate legal teams – are currently very busy indeed. Too busy to do anything, other than work (or quit). And certainly too busy to change.

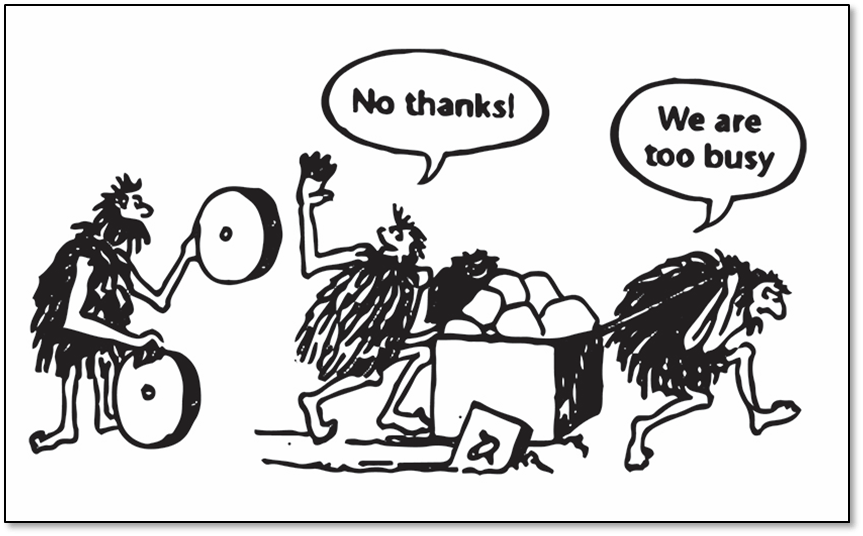

This is just another spike in a long-running trend. Anyone involved in innovation and change in a traditional law firm partnership will be accustomed to dealing with lawyers who are ‘too busy’ to think about doing things differently. It is a genuine fact of law firm life, and overcoming this obstacle is part of the job. But when law firms are very busy, the appetite for change – whether it be investing in new technologies, exploring new ways of delivery, proposing customer-centric pricing models or developing client-facing products – is seriously diminished.

The Thomson Reuters Institute 2022 Report on the State of the Legal Market confirms that this is a genuine issue. The report contains a rather depressing infographic showing those non-billable activities that lawyers consider to be “under-popular”. According to the report, lawyers expect responsibility for these under-popular activities to be delegated “to support professionals and to those partners who might specifically wish to be involved”. What are these distracting and unnecessary activities? They include: tech implementation, innovation, pricing models, well-being and, shockingly, diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I). These under-popular activities all have something in common – they contribute, in one way or another, to changing the status quo. Conversely, ‘strategy and planning’ (whatever that means) is a highly popular activity, as are ‘client relationships’ and ‘practice development’. The infographic forces the uncomfortable conclusion that, for busy private practice lawyers, everything, other than direct client work, is someone else’s job. The lawyers just don’t have time for it.

There is, however, a risk associated with just getting on with the job. If law firms are too busy to change, then it is reasonable to assume that they are also too busy to listen – to their people, to their clients, and to other stakeholders in the wider world. This approach is both dangerous and outmoded. Recall Kotter’s description of organisations that successfully manage change – those organisations develop an adaptive culture, described as one that “highly value[s] the interests of all the enterprises’ major constituencies, particularly customers, stockholders, and employees”. This description could be lifted from the vision statement of any number of law firm corporate clients. Recent years have seen the rise, in the corporate world, of the concept of stakeholder capitalism, and a renewed corporate focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. Corporates are putting ESG at the heart of their strategy, and not only for reasons of ethics and conscience; in a world in which reputations can be made or broken by a single tweet, being alert to ESG issues can be an important source of corporate value creation. If they are to remain trusted advisers to their clients, law firms need to take a similar, purpose-driven approach to their own businesses.

Being too busy to change is no longer a valid excuse; it is a short-sighted and short-term response in a world in which managing change must be part of the job. Law firms need to listen to and learn from their clients, and make time to address fundamental structural issues that will improve service delivery, deliver customer value, elevate the employee proposition (not just for lawyers) and cultivate a healthy and diverse organisational culture. If these issues are considered to be under-popular, then law firms must work to convert them into what the TR Report describes as a “vocation”, an activity that “feels like a calling and people get a lot out of … most are happy to be involved”. Why? Because although law firms don’t like to think of themselves as suppliers, or of their clients as customers, they are, of course, part of a supply chain and will be assessed by their clients accordingly. Just as legal tech providers, when selling to law firms, need to establish themselves as creditworthy and reputationally robust, so law firm clients need to demonstrate to their clients that they are focussed on critical internal issues such as the diversity and mental health of their people. The hard facts are that corporate clients will increasingly be unable to do business with suppliers and partners that do not meet minimum ESG standards. These standards are already far reaching, and are likely to become increasingly stringent, extending to the firm’s DE&I credentials, to an analysis of which other clients the firm represents, and to how the firm treats its people.

Change is not beyond law firm capabilities. Law firms can be responsive, and adaptive, and move quickly to address changing client and stakeholder needs. There are many examples: the response to the BREXIT referendum result (which required some rapid and radical organisational restructuring); the response to COVID (law firms moved quickly to remote working); and the response to the invasion of Ukraine (many firms moved rapidly to sever ties with Russian clients and offices). In each of these examples, however, change is reactive, catalysed by a crisis, rather than the product of measured, strategic decision making to future-proof the organisation. Issues of employee wellness, of DE&I, of innovation, strategic pricing and digital transformation – all those under-popular activities – may not feel as urgent as a crisis, but they are critical to the long-term health and adaptive power of an organisation. These issues require urgent attention, at all levels of the firm. Change cannot be achieved by a top-down mandate. It must be a team effort, achieved by engaging the lawyers and other allied professionals within the law firm (HR, Marketing, Finance, DE&I). These activities need to become part of the firm’s core delivery, as essential and as valued as fee-earning activities.

A buoyant market and healthy revenues present an opportunity to invest in clients, and in people, for the long term. Rather than simply getting on with the job, law firms should take this opportunity to engage the entire firm in a radical rethink of purpose and priorities. It’s the right time to listen to customers, and to make time for change.

References

- John P Kotter, Vanessa Akhtar and Gaurav Gupta, Change: How Organizations Achieve Hard-To-Imagine Results in Uncertain and Volatile Times, Wiley, 2021.

- www.thomsonreuters.com/en-us/posts/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/01/State-of-Legal-Market-Report_Final.pdf.