Dr. Alexandra Andhov is Associate Professor of Corporate Law and Law and Technology at the University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Law and Founder & Director of Copenhagen Legal Tech Lab

In the rapidly evolving landscape of novel technologies, artificial intelligence might have a major impact on the legal profession. AI is on all lawyers’ minds. Some of us actively use and play with it, while others and their law firms prohibit using publicly available generative AI. Recently, a new Cisco survey showed that over a quarter of companies have implemented generative AI bans among their staff. This survey, conducted among 2600 security professionals in 12 countries, also revealed that two-thirds of those questioned have imposed limitations on what information can be entered into LLM-based systems or fully prohibited the use of specific applications.

This study has nudged us to consider why some lawyers have opened their arms towards generative AI solutions while others remain sceptical.

Therefore, in this short blog post, we will look into the current “market leader” – ChaptGPT and answer the key questions that every lawyer should know:

- How does ChatGPT work?

- Where does the data come from?

- What happens to the data that I input with my questions?

Throughout the post, we will share further data and resources that lawyers might find helpful in deciding whether to use ChatGPT (or like) and “how” to utilise it.

How Does ChatGPT work?

Launched by OpenAI, ChatGPT represents a significant leap in large language model technology, offering various capabilities. ChatGPT, a variant of the larger Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT) series, debuted in November 2022. It quickly grasped attention for its ability to “understand” and generate human-like text, making it thus an interesting tool in fields that heavily rely on language and communication – like law. It is a good tool for text organisation, summarisation, and generation. Whether it is to help you summarise text, re-write an email or improve your language while writing longer texts, it does – for a technology – an impressive job. It employs advanced techniques in machine learning and natural language processing.

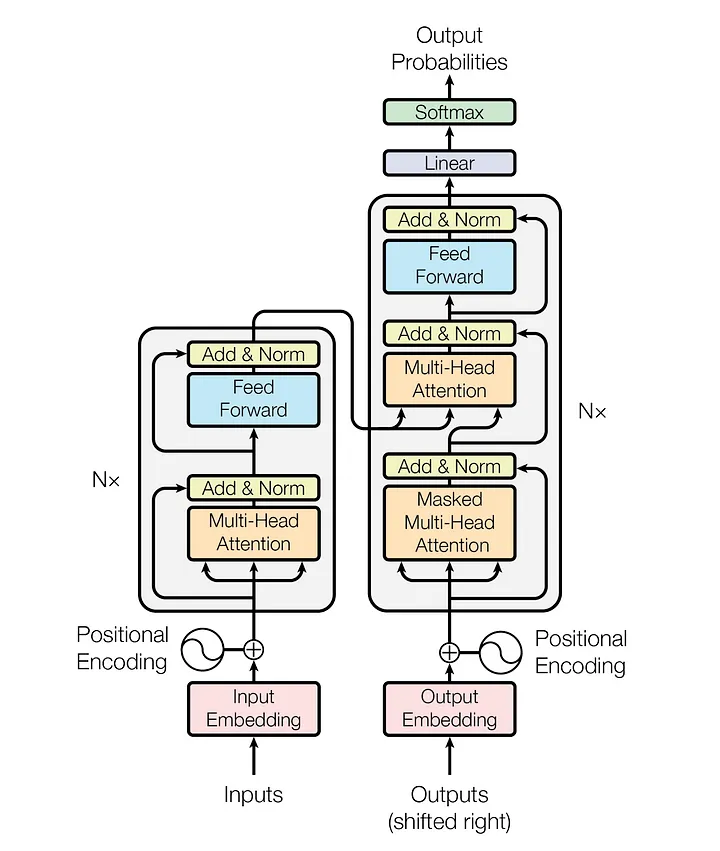

At its core, ChatGPT utilises a type of artificial intelligence called GPT – Generative Pretrained Transformer. This technology is designed to understand and respond to user inputs by analysing vast amounts of textual data, learning patterns of language usage, and context. The transformer architecture is a type of neural network that aims to simulate the human processing of language through layers of interconnected nodes. This type of underlying architecture was proposed for the first time in 2017 in a paper named ‘Attention Is All You Need’, which suggested the following model architecture, whereas the ‘Nx’ refers to the number of layers a particular transformer implements. Usually the transformers have many layers, which carry out different tasks but apply the same method.

The OpenAI’s GPT transformer uses a different structure. For example, the GPT-2 has 12 layers of transformers, each with 12 independent attention mechanisms, called ‘attention heads’, thus providing 144 (12×12) distinct attention patterns. The transformer is like a multi-layered brain, with each layer containing different mini-brains or sub-layers. There are two critical types of mini-brains: one is figuring out which words in a sentence are the most critical (self-attention layer), and the other is for shaking up the information in complex ways (feedforward layer). These parts work together to help the transformer understand how words in a sentence relate.

Each attention pattern corresponds to a linguistic property captured by the model. The GPT also has a layer that allows it to focus on specific words or phrases to understand their relevance better and provide more accurate responses. The transformer architecture processes sequences of words by using “self-attention” to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence when making predictions.

Think of a transformer like a puzzle enthusiast working on a huge jigsaw puzzle, with each piece representing a word in a sentence. The task is to assemble the puzzle so that all the pieces fit together to create a coherent picture, which in language terms means a coherent sentence or text.

What does the enthusiast do first? They will try to determine the frame and then the patterns that are on the puzzle. This means, they will bring together pieces that are of a particular shape and color. Based on the similarities between the pieces it is possible to determine whether these belong together. Seeing more pieces together, the enthusiast continues, they notice patterns: certain colors (topics) tend to cluster, edges (sentence beginnings and endings) frame the picture, and there are spots where specific shapes (syntactic structures) always fit. This is the transformer learning the linguistic properties and patterns.

The enthusiast uses these patterns to predict where the next piece should go. If they put a piece down and it fits perfectly, making the picture more complete, they know they’ve made a good choice. With GPT, when the models were trained, there would be an external evaluator who would review whether the pieces truly fit or not, teaching the model which patterns and linguistic properties work and which do not.

Ultimately, the GPT works as a puzzle enthusiast with 12 layers, each containing 12 different tools, or ‘attention heads,’ that help it focus on various parts of a sentence. Imagine having 144 pairs of eyes, each looking at sentences from different angles. These ‘eyes’ pick up on various language cues, such as whether a word is a noun or a verb or if it’s the subject or object of a sentence.

For example, in the sentence “Jane threw the ball,” one attention head might focus on “Jane” to figure out who is doing an action, while another might zero in on “threw” to understand the action taking place. Another might link “the ball” to “threw” to see what was affected by the action.

A special part of GPT-2 acts like a highlighter, marking essential words or phrases to grasp better what they mean in context. It’s similar to how you might highlight parts of a legal document that seem crucial for understanding the whole text.

The ‘self-attention’ feature of GPT-2 is like a skilled reader looking back at the text’s previous parts to understand new information. For instance, if a later paragraph in a contract refers to “the debtor,” the model scans earlier sections to remember who the debotr is. This way, GPT-2 keeps track of all the words and how they relate, ensuring it understands the whole story or argument.

The underlying mechanism of ChatGPT is probability. This probability takes place on each layer. It does not “understand” the words that we use. It is built on mathematical models that involve learning the probabilities of word sequences. The model is exposed to an extensive text corpus during its training phase. Through this exposure, it learns how words and phrases are typically arranged in human language. This is also why it performs better in English than in other languages, as most of the training text was in English. Moreover, the models must reflect the differences in syntax when analysing and responding to text in other languages.

The model starts with no prior knowledge, initially generating random responses. However, it learns to predict words in a sentence more accurately through iterative training. For example, in completing a sentence like “instead of turning left, she turned ___,” the model initially might guess random words. Over time, it learns from various contexts, improving its ability to predict the most contextually appropriate word, such as “right,” “around,” or “back.”

This learning process is achieved by adjusting numerous parameters or weights within the model. These weights, essentially large strings of numbers, are further fine-tuned during training. Each parameter influences how the model interprets and generates language. Contrary to storing or copying information, the model adjusts these weights to reflect the patterns it has learned. As a result, the model becomes more adept at predicting and generating language that aligns with our (human) use.

Moreover, this technology is akin to advanced auto-complete systems used in search engines, smartphones, and email programs but operates on a much more complex scale. ChatGPT’s ability to generate coherent and contextually relevant text is a testament to modern machine learning models’ well-designed architecture and training processes. This technology continuously evolves, leading to more sophisticated and accurate language generation models.

Where Does the Data Come From?

According to OpenAI, ChatGPT was developed using three critical sources of data:

- Information that was publicly available on the Internet

- Information that OpenAI licensed from third parties; and

- Information that OpenAI or human trainers provided.

For this discussion, we will assume that this is indeed true, and that OpenAI did not use any other data. One of the primary methods employed by OpenAI for data collection is web scraping, a process that involves the automated retrieval of information from the internet. This technique enables the collection of large volumes of data from various web sources – websites, blogs, news articles and forums, which can then be processed and analysed. The goal is to create a comprehensive corpus of text that reflects the wide variety of language used in different contexts and for various purposes so that the model can learn. This variety helps the language models understand and predict a broad array of linguistic structures and styles, enabling them to generate text that is contextually relevant and stylistically appropriate.

For the language models to be effective, the data collected would need to be “pre-processed” and cleaned. This could involve removing duplicates, correcting errors, and standardising formats to ensure consistency. Furthermore, the data would undergo tokenisation, where the text is broken down into smaller units like words or phrases, which serve as the building blocks for model training.

For the OpenAI to stay current and reflect the most recent “realities”, the system must be constantly crawling the web and updating its datasets. This ensures that the models remain relevant and can understand contemporary slang, emerging terminologies, and the latest factual information, thereby maintaining their utility and accuracy over time. However, we see that many entities, such as the New York Times or the Guardian, are actively fighting against web scraping and implementing techniques through which they limit the use of their data by OpenAI. Just a few weeks ago, the New York Times filed a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft for unauthorised use of published work to train the language model. The hope is that the lawsuit will clarify the rights and responsibilities of copyright holders and AI companies.

As lawyers, we must recognise that just because the information is publicly available on the Internet, it does not mean that it can be used without any consideration and even commercialised. Even if OpenAI did not seek information behind paywalls or from the “dark net”, in many instances, national copyright laws will be attached to the information.

Even if the US has a doctrine that when information is in the public sphere, it’s no longer private, which has in theory allowed OpenAI to use publicly available information, this is not the case across the EU Member States. With the EU AI Act being in the final stages of negotiations, according to its most recently disclosed formulation, it is highly foreseeable that the AI Act will require AI developers to disclose copyright compliance policies. However, the specifics of such disclosure are to be seen.

Where Does Your Data Go?

One of the more critical questions that, as lawyers, we need to know the answer to is what happens with the data we share with ChatGPT. Whether it is the name of a client when drafting the email or whether it is some confidential data regarding the M&A. Most presumably, a lot of the data will be seen as limited in their value, but we must be aware that sometimes, just one piece of information might become extremely valuable. As lawyers, we work most presumably with a lot of information that, if smartly combined, might be detrimental to our clients. This is one of the reasons that nudge the law firms to ban generative AI by their lawyers, as indicated in the Cisco survey.

The answer to where the data goes is that the ChatGPT saves all the conversations and data in the chat history. Even if you choose the settings that you do not wish for the chat to keep, it will still continue to store the history. First and foremost, if you choose the setting that you do not store the data, it will continuously bug you to change it and the functionality of the ChatGPT will radically decrease and it will be impossible to conduct any longer sessions where one would be adding new queries or questions. This major limitations would suggest that the architecture of the system has been designed as to always store the data and utilise it for re-learning. If such major hiccups occur, most presumably, there is a problem with the underlying technological logic.

However, the conversations are not the only data we are handing over when we use ChatGPT. OpenAI also has access to the following:

- Phone number

- Geolocation data

- Network activity information

- Commercial information, e.g. transaction history

- Identifiers, e.g. contact details

- Device and browser cookies

- Log data (IP address etc.)

In addition, OpenAI can extract information about you if you interact with social media pages based on the aggregated user analytics made available to businesses by the likes of Facebook, Instagram, and X. Therefore, if this information were ever combined in the hands of specific entities that would like to find particular information, they might be able to easily determine your account on OpenAI and possibly see the shared discussions.

A bit more concerning is that in its privacy policy, OpenAI stipulates that the company discloses the information listed above to its “affiliates, vendors and service providers, law enforcement, and parties involved in transactions”. This unspecified list combined with unspecified purpose should undoubtedly be questioned by the EU data protection regulations.

Final Considerations

Generative AI is an interesting tool and helps with some types of tasks. In the same way that it can also be helpful and insightful for many of my students when writing essays, it can be supportive when writing a legal memorandum or potentially court submissions. Nonetheless, it is essential to scrutinise the reliability of this technology. We know from many stories and studies that the ChatGPT can produce erroneous information, fabricate data, and cite non-existent sources and case law. The battle over the data on the Internet is far from over, which can affect the tool’s accuracy. Moreover, some research shows that the newest GPT 4.0. may experience performance degradation over time. Thus, use the ChatGPT wisely and protect personal or highly valuable data. Consider using other AI legal tech tools specifically designed to address the above issues, ensuring the integrity and provenance of the data used.